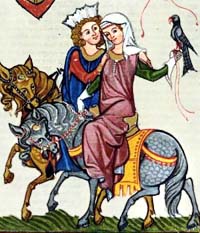

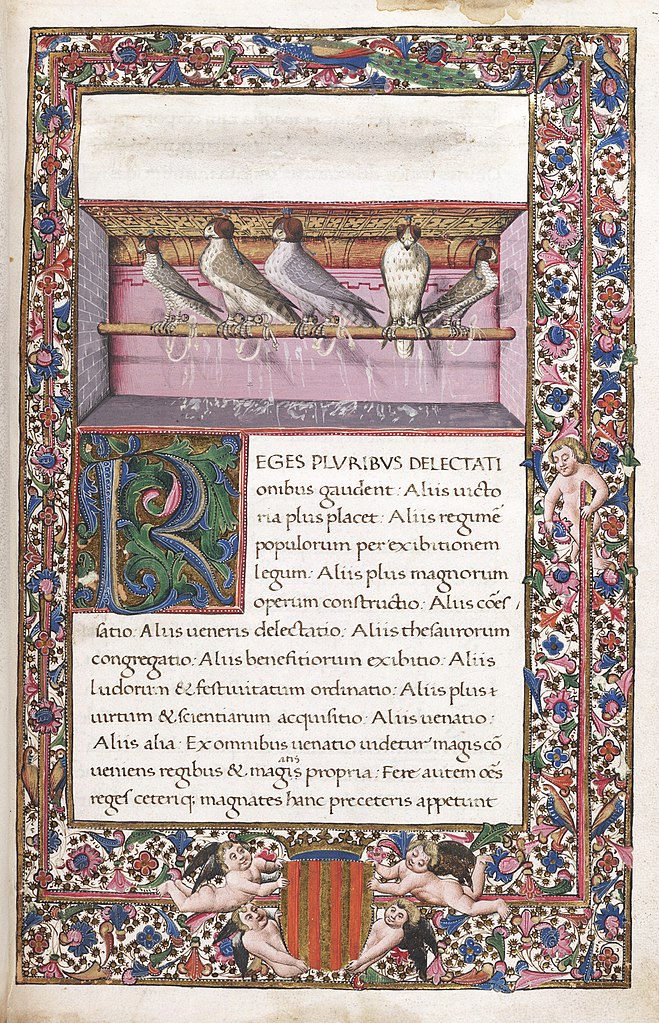

Medieval Falconry and Hawking took advantage of trained birds of prey to hunt small wild game such as squirrels and rabbits, and other birds.

A falconer would fly a falcon, an Austringer, a hawk (Accipiter), or an eagle (Aquila).

Falconry became a regulated, revered, and popular sport and status symbol among the nobles and the clergy of medieval Europe. In some religious orders, falcons were even taken into religious services.

Falcons were so highly valued that they were worth more than their weight in gold.

History of Falconry

It’s believed that falconry’s art may have begun in Mesopotamia in approximately 2,000 BC. With cases also found in northern Altai, western Mongolia (for Mongol tribes, the falcon was a symbolic bird). Figures of a falconer on horseback were also described on Kyrgyz’s rocks in Central Asia dating back to the 7th century AD.

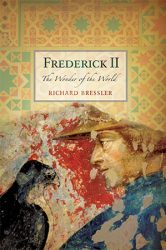

Falconry was introduced to Europe probably around AD 400 when the Huns and Alans invaded from the east. It’s believed that Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (King of Sicily, Germany, and the Roman Empire) obtained firsthand knowledge of Arabic falconry when he got a copy of the Arabic author Moamyn‘s manual on falconry and had it translated into Latin by Theodore of Antioch. Moamyn’s work is largely based on the Kitāb al-ṭuyūr (كتاب الطيور), the Book of Birds or Book of flight cycles (patterns) of Birds), a more extensive work by al-Ghiṭrīf ibn Qudāmah al-Ghassānī from the early ninth century.

King Frederick II wrote what is now widely accepted as the first comprehensive book of falconry, the De arte venandi cum avibus (“The Art of Hunting with Birds”). The treaty took him over thirty years to complete and is considered one of the first scientific works on birds’ anatomy and a founding book of ornithology.

Falconry soon became a popular sport and status symbol among medieval Europe’s nobles, as it required a commitment of time, money, and space.

The Value of a Falcon

Falcons were highly valued. During a crusade in the late fourteenth century, the Ottoman Sultan Beyazid captured the son of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. 200,000 gold ducats were offered for ransom to recover the man and turned down. What Beyazid wanted (and was given) was something more precious: Twelve white gyrfalcons.

Falcons were also used as offerings of peace. In 1276, the king of Norway sent eight gray and three white gyrfalcons to Edward I as a sign of peace. A trained peregrine was the falconer’s most treasured possession and one of the merchants’ most costly trade goods.

Harming falcons (or their eggs or newly hatched young) was viewed as a crime with severe penalties. A fourteenth-century bishop of Ely, for example, excommunicated the thieves who stole the falcons he had left in the cloister of his church.

Falconry in Great Britain

The first documented English falconer was the Saxon king of Kent, Ethelbert II of East Anglia, in the eighth century. Alfred the Great and Athelstan of Kent in the ninth century also practiced falconry.

Falconry was so important to English society that one could rarely walk down the medieval streets without seeing someone with his or her falcon perched on hand on wrist.

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, the gyrfalcon and new subspecies of the peregrine were introduced in England, and for the next six centuries falconry steadily increased in popularity. While the “long-winged hawks” (gyrfalcons and peregrines) were reserved for the nobility, the average citizen usually kept sparrowhawks and goshawks. These birds had little use in procuring food for its owner.

The Stuarts were particularly fond of the sport of falconry, with Henry VIII being considered by some as the most important falcon advocate since Federick II.