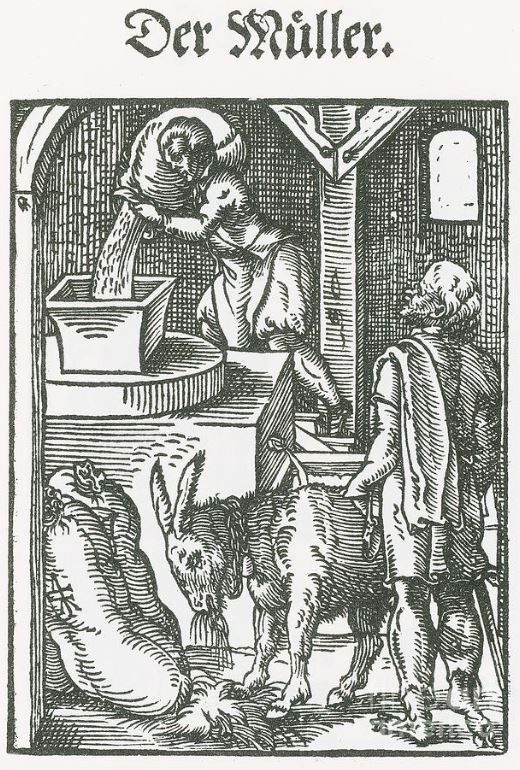

Medieval millers operated grain mills, which were used to grind wheat, barley, and oats into flour. Millers were an essential component of the community in the Middle Ages, as grain was a staple food, and flour was used to bake bread – one of the most important foods of the time.

In addition to grinding the grain, a miller was also responsible for maintaining the mill and ensuring that it remained in good working order.

Millers were some of the most important tradesmen in the Middle Ages. So, let’s learn a little more about this medieval profession and what life was like for medieval millers in Europe.

History of Millers

Millers have been grinding grain for as long as we’ve grown wheat, barley, and oats. In fact, milling is one of the oldest occupations, as hunter-gatherer communities also needed to grind their food to make consumption easier.

The earliest mills in Europe used a horizontal wheel. These were known as clack mills or Norse mills. In the middle ages, though, a more efficient overshot type was introduced.

Water mills were an important technology in medieval Europe, as they allowed for efficient and large-scale production of flour, which was an essential food item at the time.

Medieval Milling Technology: How Did Mills Work in the Middle Ages?

Medieval mills were powered by various energy sources, including water, wind, and animal power. The most common type of medieval mill was the water mill, which used the energy of flowing water to power the millstones that ground grain into flour.

Water mills typically consisted of a large wooden or stone building known as the millhouse, which housed the machinery for grinding grain. The millhouse was often located near a river or stream, and water was diverted from the river to power the mill’s waterwheel. You can see many of them still today!

This is how a watermill worked: The waterwheel turned a large horizontal shaft that ran the length of the millhouse. Attached to the shaft were gears and cogs that turned the grinding stones, which were housed in a separate room or chamber.

The grinding stones were typically made of a hard, abrasive material such as granite or sandstone. The top stone, known as the runner, rotated over the stationary bottom stone, or bedstone. Grain was fed into the mill’s hopper, which funneled it down between the two stones. As the runner turned, it ground the grain into flour, which was collected in a bin or sack.

The miller was responsible for adjusting the gap between the stones to achieve the desired level of fineness for the flour. This was typically done by adjusting the position of the top stone using a lever or mechanism.

The Life of a Medieval Miller

The miller’s job was to receive the grain from local farmers, weigh it, and grind it into flour. The grain was poured into the mill’s hopper, which fed it down into the grinding stones. The miller had to adjust the millstones to ensure that the grain was ground to the appropriate consistency.

Life for a medieval miller was somewhat challenging, but like anything in life, could also be rewarding. As the operator of a vital piece of technology in medieval Europe, the miller played an essential role in the local community and was often a respected figure. However, the work of a medieval miller was physically demanding and could be dangerous, too. The miller had to be skilled at operating the mill’s machinery and maintaining the grinding stones, which could be heavy and difficult to move. They also had to be able to handle the sacks of grain, which could weigh hundreds of pounds.

The miller had to work long hours, often from dawn until dusk, to keep the mill running smoothly. They had to be on call at all times, as local farmers would bring their grain to the mill as needed. This meant that the miller’s workday was often unpredictable and could be interrupted at any time.

In addition to the physical demands of the job, the miller also had to deal with issues of honesty and trust. It was not uncommon for millers to be accused of skimming off some of the grain brought to them for grinding or for providing poor-quality flour to their customers.

Despite these challenges, being a successful miller could be a lucrative profession. The miller could charge fees for their services, as well as take a portion of the grain as payment. In addition, the miller could sell the flour they produced to local bakers and other customers, generating additional income.

Overall, life for a medieval miller was a mixture of hard work, technical skills, and social responsibility.

Books about Medieval Life

More Medieval Occupations

Medieval Minstrel

Medieval minstrels sang, played musical instruments, and told engaging stories. Here’s what life was like for a minstrel in the Middle Ages.

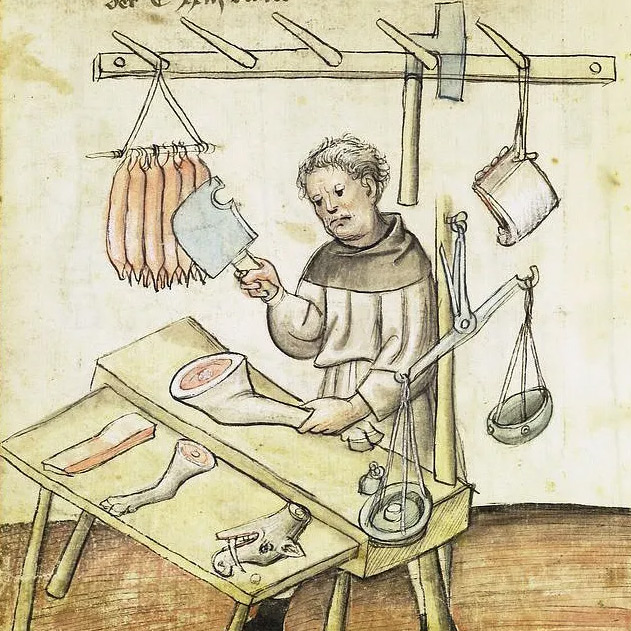

Medieval Butcher

Middle Ages butchers prepared meat, fish, and fowl for the people in a castle or a city. They sometimes had stalls in a marketplace.

Medieval Wheelwright

Medieval candlemakers made candles from materials such as fat, tallow and beeswax.

Medieval Shoemaker

Medieval candlemakers made candles from materials such as fat, tallow and beeswax.

Medieval Shipwrights and Shipmaking

Being a sailor in the middle ages meant living a lonely and difficult life, as they would often set sail for months or even a year at a time.

Medieval Stable Master and Grooms

Medieval Stable Master and Grooms were responsible for horses and stables.