The Ruin is a poem in Old English that evokes the former glory of a ruined Roman city believed to be Bath. The poem was written in the 8th or 9th century by an unknown author and published in the Exeter Book, an Anglo-Saxon anthology of riddles and poems.

The Ruin talks about the former glory of a ruined Roman city and its decayed and broken buildings, such as towers, baths, walls, and palaces. The writing consists of forty-nine lines, some of which are illegible, and there’s an agreement that it refers to the Roman city of Bath, in Somerset, England. Part of it, “brosnað enta geweorc,” or “the work of giants is decaying,” was used by J. R.R. Tolkien for the tree-men Ents in The Lord of the Rings.

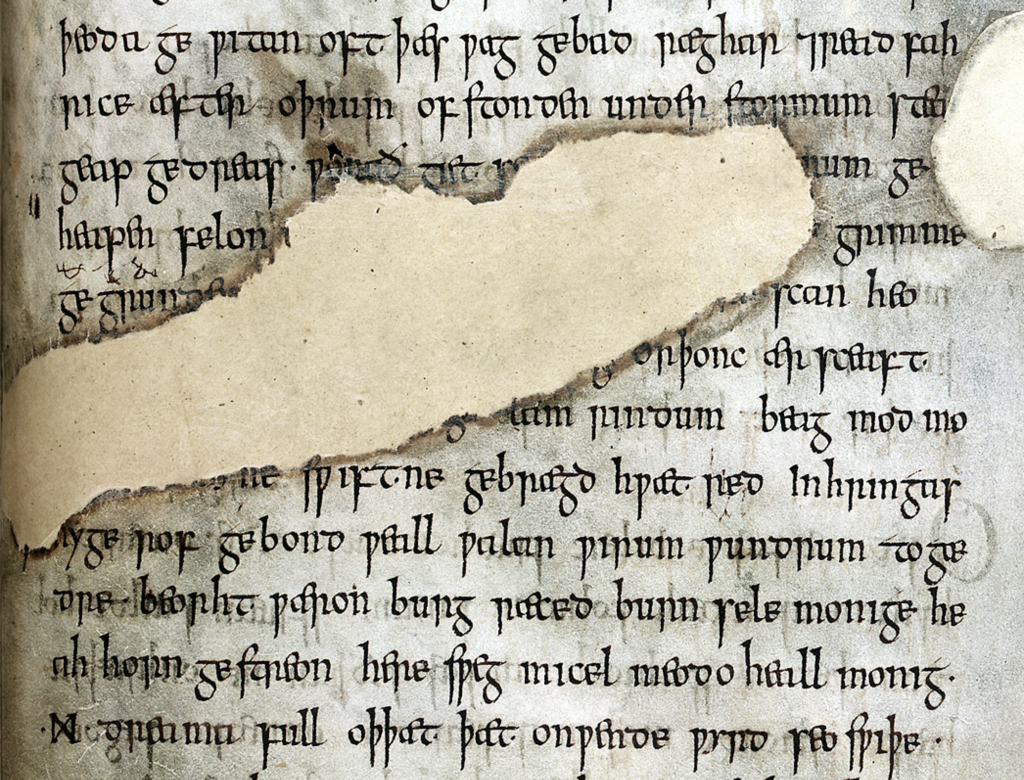

Ironically, the poem – which talks about destruction and oblivion – was written on a piece of the manuscript that suffered considerable damage in a fire. Quite an eloquent image!

The Ruin

Original Old English

Wrætlic is þes wealstan, wyrde gebræcon;

burgstede burston, brosnað enta geweorc.

Hrofas sind gehrorene, hreorge torras,

hrungeat berofen, hrim on lime,

scearde scurbeorge scorene, gedrorene,

ældo undereotone. Eorðgrap hafað

waldend wyrhtan forweorone, geleorene,

heardgripe hrusan, oþ hund cnea

werþeoda gewitan. Oft þæs wag gebad

ræghar ond readfah rice æfter oþrum,

ofstonden under stormum; steap geap gedreas.

Wunað giet se …num geheapen,

fel on

grimme gegrunden

scan heo…

…g orþonc ærsceaft

…g lamrindum beag

mod mo… …yne swiftne gebrægd

hwætred in hringas, hygerof gebond

weallwalan wirum wundrum togædre.

Beorht wæron burgræced, burnsele monige,

heah horngestreon, heresweg micel,

meodoheall monig mondreama full,

oþþæt þæt onwende wyrd seo swiþe.

Crungon walo wide, cwoman woldagas,

swylt eall fornom secgrofra wera;

wurdon hyra wigsteal westen staþolas,

brosnade burgsteall. Betend crungon

hergas to hrusan. Forþon þas hofu dreorgiað,

ond þæs teaforgeapa tigelum sceadeð

hrostbeages hrof. Hryre wong gecrong

gebrocen to beorgum, þær iu beorn monig

glædmod ond goldbeorht gleoma gefrætwed,

wlonc ond wingal wighyrstum scan;

seah on sinc, on sylfor, on searogimmas,

on ead, on æht, on eorcanstan,

on þas beorhtan burg bradan rices.

Stanhofu stodan, stream hate wearp

widan wylme; weal eall befeng

beorhtan bosme, þær þa baþu wæron,

hat on hreþre. þæt wæs hyðelic.

Leton þonne geotan

ofer harne stan hate streamas

un…

…þþæt hringmere hate

þær þa baþu wæron.

þonne is

…re; þæt is cynelic þing,

huse …… burg….

Modern English

This masonry is wondrous; fates broke it

courtyard pavements were smashed; the work of giants is decaying.

Roofs are fallen, ruinous towers,

the frosty gate with frost on cement is ravaged,

chipped roofs are torn, fallen,

undermined by old age. The grasp of the earth possesses

the mighty builders, perished and fallen,

the hard grasp of earth, until a hundred generations

of people have departed. Often this wall,

lichen-grey and stained with red, experienced one reign after another,

remained standing under storms; the high wide gate has collapsed.

Still the masonry endures in winds cut down

persisted on__________________

fiercely sharpened________ _________

______________ she shone_________

_____________g skill ancient work_________

_____________g of crusts of mud turned away

spirit mo________yne put together keen-counselled

a quick design in rings, a most intelligent one bound

the wall with wire brace wondrously together.

Bright were the castle buildings, many the bathing-halls,

high the abundance of gables, great the noise of the multitude,

many a meadhall full of festivity,

until Fate the mighty changed that.

Far and wide the slain perished, days of pestilence came,

death took all the brave men away;

their places of war became deserted places,

the city decayed. The rebuilders perished,

the armies to earth. And so these buildings grow desolate,

and this red-curved roof parts from its tiles

of the ceiling-vault. The ruin has fallen to the ground

broken into mounds, where at one time many a warrior,

joyous and ornamented with gold-bright splendour,

proud and flushed with wine shone in war-trappings;

looked at treasure, at silver, at precious stones,

at wealth, at prosperity, at jewellery,

at this bright castle of a broad kingdom.

The stone buildings stood, a stream threw up heat

in wide surge; the wall enclosed all

in its bright bosom, where the baths were,

hot in the heart. That was convenient.

Then they let pour_______________

hot streams over grey stone.

un___________ _____________

until the ringed sea (circular pool?) hot

_____________where the baths were.

Then is_______________________

__________re, that is a noble thing,

to the house__________ castle_______

Setting and Possible Location

There have been several theories as to which city is depicted in the poem The Ruin.

In 1865, Heinrich Leo suggested it could be Bath’s city, while others have hinted it could be Chester or even a fictional city. The consensus is that Leo is correct. Three features point in this direction. One is the mention of a hot spring (not artificially heated water), the second is the reference to many bathing halls and the last of a circular pool. The way Bath probably looked in the eighth century is probably also similar to that of the city described in the poem.

Themes

Because the author is referring to the ruins hundreds of years after these were abandoned, several interpretations seem to reflect not so much the physical appearance of the building but an evocative effort to bring, as William Johnson stated, “stone ruins and human beings into polar relationships as symbolic reflections of each other“. According to Johnson, The Ruin is a metaphor for human existence and the fall of beauty – basically how everything must come to an end. This once gorgeous structure was reduced to rubble, just like the Roman Empire.

Other authors such as Arnold Talentino have seen the poem as an angry or realistic condemnation of those responsible for the destruction. This view would fit a more common Christian theme, the idea that the city’s inhabitants caused its fall and that “the crumbling walls are, in part at least, the effect of a crumbling social structure“.