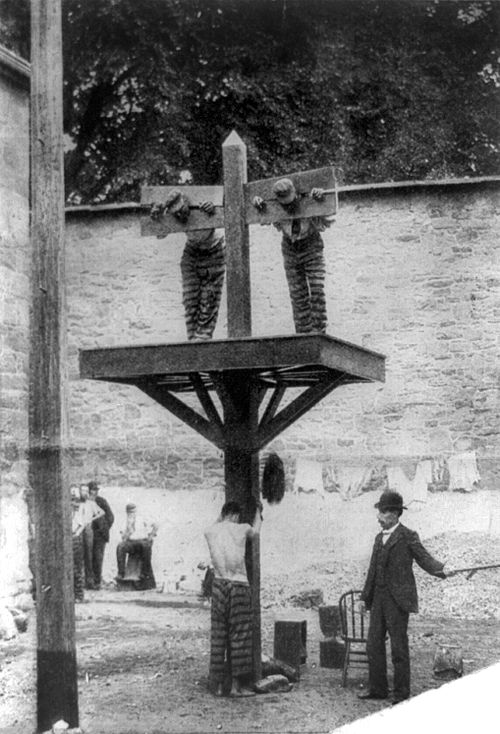

The pillory and the stocks were among the most familiar sights of public punishment in medieval and early modern Europe. Unlike the elaborate torture devices that fill modern imagination, these were real, common, and deeply woven into everyday systems of justice.

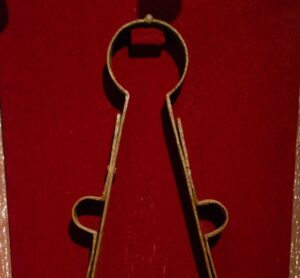

The stocks were usually a simple wooden frame with holes that locked a person’s ankles in place, forcing them to sit or lie in an uncomfortable position for hours or even days. The pillory was harsher and more exposed: a standing frame that secured the head and hands, leaving the person upright, trapped, and fully on display.

Both devices were typically placed in the busiest public spaces—market squares, crossroads, outside churches—where the maximum number of people could witness the humiliation. Their power came not from secrecy or machinery, but from visibility. They were punishments designed to turn the community itself into part of the sentence.

The Pillory and Stocks in Medieval Times

These punishments were not primarily about physical injury in the way torture was. Their purpose was shame. To be locked in public meant being marked as a wrongdoer before neighbors, employers, and family.

Crowds were an expected part of the ordeal. People might jeer, insult, or pelt the prisoner with rotten food, mud, or stones. Sometimes the treatment could become violent enough to cause serious injury or even death, though authorities did not always intend that outcome. The unpredictability of the crowd was part of the fear: once placed in the pillory, a person was at the mercy of public reaction.

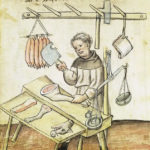

The crimes that led to these punishments were often those seen as social disruptions rather than capital offenses: petty theft, fraud, selling bad goods, drunkenness, slander, or other acts that undermined trust within the community. In this sense, the pillory functioned as a tool for enforcing moral and economic order. A dishonest baker or merchant could be punished not only with discomfort but with lasting damage to their name.

Were the Pillory and Stocks Real?

Yes, the pillory and the stocks were completely real, and they are among the best-documented forms of punishment in medieval and early modern Europe.

Unlike many infamous “torture devices” that are exaggerated or mythical, these were:

- Common civic punishment tools

- Legally authorized

- Used publicly in town squares

- Recorded in court documents and local laws

- Physically preserved (many originals still exist in museums and even some towns)

They were used for everyday crimes like theft, fraud, drunken disorder, and slander. Because these devices were so public, they also served as warnings. They were meant to deter others through spectacle, reminding everyone of the consequences of breaking local law. Justice was not hidden behind prison walls; it was performed in the open, where it reinforced authority and communal norms.

A Change in Systems

Over time, as legal systems changed and imprisonment became more common, punishments like the pillory and stocks began to decline. Public humiliation came to be seen as disorderly, cruel, or incompatible with newer ideas about human rights and state-controlled justice. By the nineteenth century, many countries abolished them, though they lingered in some places longer than people expect.