We all know what Halloween is today, but did people in the Middle Ages also celebrate this tradition in some way?

The word was first spelled “Halloween” in 1789 when it appeared in a poem by celebrated Scottish writer Robert Burns. The word is a contraction, and the clue can be found in Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. When expanded, Halloween means “All-Hallond Evening,” meaning a festivity before a holiday. So what exactly was All Hallond, or as you might know it today, All Hallows’ Day?

All Hallows' Day and Samhain

All Hallows’ Day is also referred to as All Saints’ Day, a day (November 1st) to celebrate the saints with a feast. As Aelfric of Eynsham states around the year 1000: “se monað ongynð on ealra halgena mæssedæg,” or “the month begins on the day of the mass for All Saints.”

The day was instituted, like many others, to redirect pagan beliefs. All Saints’ Day coincides, unsurprisingly, with the Celtic New Year or Samhain (which, since we’re talking meanings, signifies summers’ end and is pronounced “sow-in”). Two interesting facts about Samhain: It lasts three days (as all good feasts should), and it’s a festival to honor the dead.

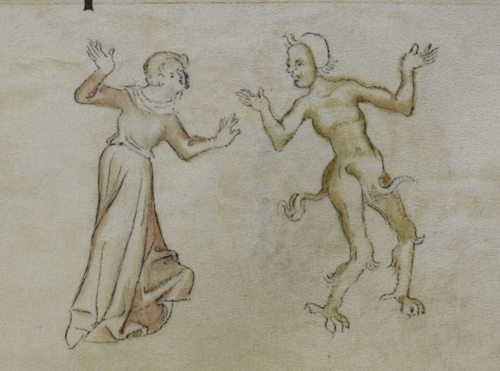

Samhain sits right at the point where the summer, or “light” part of the year, turns into winter or “dark” — or as life turns into death. In consequence, during such a day, it was considered that the borders between the worlds of the living and the dead thinned, allowing spirits to roam more freely. Much of Samhain’s imagery, and later Halloween, is related to death: Skeletons, ghosts, pale faces with big eyes.

In 1048, the Christian Church defined All Souls’ Day as November 2 and declared it a day to pray for the dead. This was particularly important after Purgatory was implemented, as people could help the dead be released from purgation. Purgatorial prayers are also the reason we have jack o’ lanterns: An existing tradition at harvest celebrations was to carve vegetables and place lit candles inside them. Since souls were also commemorated with candles, the traditions overlapped with fair success.

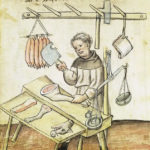

Medieval Rituals

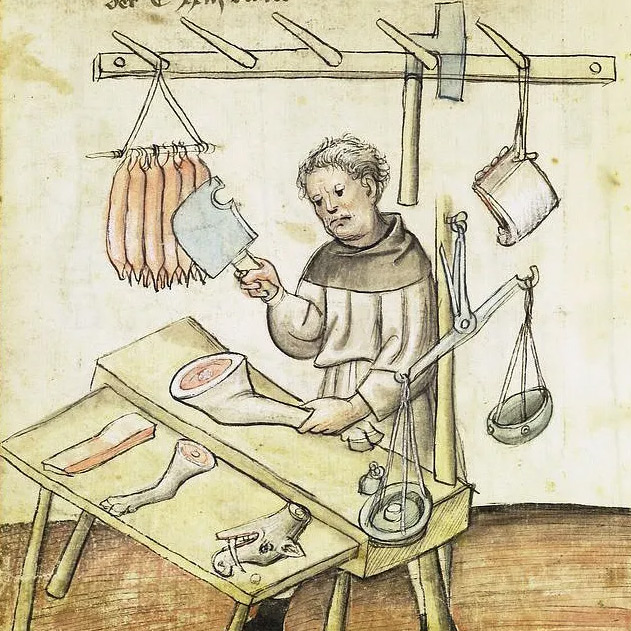

Rituals associated with Samhain included large bonfires, feasting, and dancing. These allowed assistants to communion with the dead while celebrating the harvest and sharing it with those present and those who had passed.

Samhain is believed to have been an important date since ancient times. Some Neolithic tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise around the celebration, and Samhain is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature.

Bonfires were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers and involved several rituals. At Samhain, it was believed that fairies and nature spirits needed to be helped in their crossing to ensure that people and livestock survived the winter. The dead souls were also thought to visit the homes where they used to live, seeking hospitality. For them to be welcomed at the table, feasts were served, and games and divination took place. These often involved nuts and apples.

Dressing Up

People also dressed up for the occasion and went door-to-door in disguise, often reciting verses in exchange for food. These costumes might have had the goal of hiding oneself from the nature spirits and fairies.

In some parts of southern Ireland, a “white mare” or man covered in a white sheet and carrying a decorated horse skull went from farm to farm reciting verses (in exchange for which the farmer was expected to donate food). Costumes were also worn by those who went about before nightfall collecting for a Samhain feast.

Mischief Night Pranks

“When imitating malignant spirits it was a very short step from guising to playing pranks”

There are recordings of people playing pranks during Samhain in the Scottish Highlands and Ireland. In some parts, Samhain was actually nicknamed “Mischief Night“. By the time Irish and Scottish immigrants crossed the Atlantic into North America, Halloween in Ireland had a strong tradition of guising and pranks.